farrago, n. — A confused group; a medley, mixture, hotchpotch.

MARCH 29

1918: Pearl Mae Bailey is born in Newport News, Virginia. One of the greatest singers and entertainers of the twentieth century, she conquered vaudeville, Broadway, and television. Her film performances, sadly, were too few and far between, but younger generations will always recognize her as the voice of the owl Big Mama in Disney’s The Fox and the Hound. Her Dolly Levi remains, however, the stuff of legend, partially immortalized on a surviving broadcast of The Ed Sullivan Show, including the famous monologue preceding “Before the Parade Passes By.”

***

“Where’s the kaboom? There was supposed to be an earth-shattering kaboom!”

1958: Hare-Way to the Stars debuts. The first Marvin the Martian short in five years after Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century, Hare-Way marked Bugs Bunny’s third run-in with the immortal “character wearing the spittoon.” This is by far the most visually stunning of the MtM shorts under director Chuck Jones, thanks to Maurice Noble’s stellar production design of futuristic terraces and elevators sprawling out amid some breathable pocket of space. One of the highlights is Bugs’s lazzi with the buzzardly “Instant Martians” on the rocket scooters.

MARCH 30

1746: Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes is born in Fuendetodos, Spain. Whether mammoth canvas or macabre etching, Goya fused the masterly traditions of Europe’s artistic past with an ironic modernity reflecting his own present.

***

1913: Animator and Disney Legend Marc Davis is born in Bakersfield, California. One of the famous Nine Old Men of Disney Animation, Davis worked on most of the studio’s classic features until the 1960s, when he turned his hand to the design and development of the company’s amusement park attractions. Davis was tasked with animating many of the great female characters in the studio’s canon, none greater than Sleeping Beauty‘s Maleficent (voiced by Eleanor Audley) and Cruella De Vil from One Hundred and One Dalmatians (voiced by Betty Lou Gerson). The all-to-rare Disney Family Album series did a great episode on Davis with extended interview clips.

MARCH 31

“All that is real and can be sensed is in constant contact with magic and mystery; one loses the consciousness of reality.”

1872: That prince of impresarios, that scion of sybarites, Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev is born in Selishchi.

***

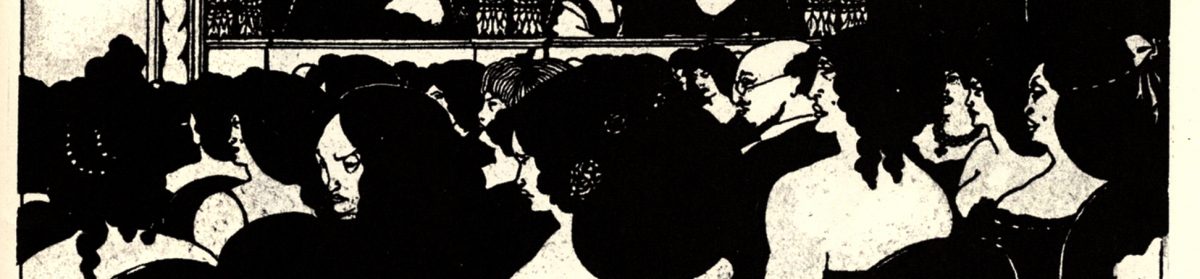

1913: A mostly unsuspecting audience gathered in the Golden Hall of Vienna’s Musikverein for a performance by the Wiener Konzertverein conducted by Arnold Schoenberg. Turmoil eventually broke out and the concert never finished.

On the Programme:

Anton Webern: Six Pieces for Orchestra, op. 6

Alexander von Zemlinsky: Four Songs after Poems by Maeterlinck (eventually Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 5 in op. 13)

Arnold Schoenberg: Chamber Symphony No. 1, op. 9

Alban Berg: Orchesterlieder, nach Ansichtkarten-Texten von Peter Altenberg, op. 4, nos. 2 and 3

Gustav Mahler: Kindertotenlieder

The performance disbanded before the Mahler, which meant that only 13 pieces were performed, always a fun number for the triskaidekaphobic Schoenberg.

***

1935: Herb Alpert is born in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles. Whipped cream for all.

APRIL 1

1919: The traditional anniversary of the founding of the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar in 1919, under the direction of Walter Gropius, here (center) with other instructors from the later school in Dessau. His manifesto for the group from that year reads thus: “So let us therefore create a new guild of craftsmen, free of the divisive class pretensions that endeavored to raise a prideful barrier between craftsmen and artists! Let us strive for, conceive and create the new building of the future that will unite every discipline, architecture and sculpture and painting, and which will one day rise heavenwards from the million hands of craftsmen as a clear symbol of a new belief to come.”

***

1932: Debbie Reynolds is born in El Paso, Texas. The last of the great broads of entertainment, Reynolds kept up a remarkable career until her final years.

APRIL 2

1891: Artist Max Ernst is born in Brühl, Germany.

***

1939: Marvin Gaye is born in Washington, D. C.

APRIL 3

Edward Carson: “The majority of persons would come under your definition of Philistines and illiterates?”

Oscar Wilde: “I have found wonderful exceptions.”

1895: Thanks to a badly-spelled calling card inscription from the Marquess of Queensbury and an aesthete’s hubris, the libel trial of Wilde v. Queensbury began on this date in 1895 at the Old Bailey. The Marquess was eventually acquitted and Wilde was left bankrupt with two further trials, incarceration, disgrace, and ruin ahead of him. Wilde’s predilections for the young poor force a difficult reckoning in our own era, where he is held up as an author as well as a martyr for gay rights. If tried today, he likely would be labeled as a sex offender.

***

1968: Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey goes into general release. It is still one of the guiding pillars of cinematic science fiction, with a tactility, believability, and mystery which has yet to be surpassed, along with the benefit of one of cinema’s most insidious villains (“Dave, my mind is going.”). It is also a musical smorgasbord, with (not uncontroversial) slices of Henry Dacre (“Daisy Bell”), more Ligeti than you’ll ever hear in most concert halls, Johann Strauss II, and, of course, Richard Strauss. I suppose there’s something to be read into Kubrick’s choice of Karajan’s recording of Also sprach Zarathustra from Decca, which the company’s management considered a sales liability and initially suppressed the connection. Much like Strauss’s tone poem, the philosophical currents of the film are, properly speaking, “freely after” Nietzsche (and a number of others). Though the notion of the “eternal recurrence” remains perhaps its deepest connection with the motif of the monolith, there’s a certain wicked resonance with the emphasis on weightlessness, the final tableau of the Star Child in orbit, and Nietzsche’s exhortation to kill the spirit of gravity.

APRIL 4

1906: Bea Benaderet is born in New York City. A presence on countless radio and television shows, she is probably known as the original voice of Betty Rubble for Hanna-Barbera, as well as countless other characters in the Warner Bros. animated shorts of the 40s and 50s. Along with the annoying bobbysoxer Red Riding Hood (“HEY, uh, GRANDMA! That’s an awfully big nose for you… TO HAVE.”), this moment may be her finest: “Goodness! Can’t a body get her shawl tied? Heavens to Betsy!”

***

“Crazy business this, this life we live in.”

1964: Sondheim’s Anyone Can Whistle opens at the Majestic Theatre on Broadway. An absurdist outing with Arthur Laurents, it only lasted for 9 performances before closing. Whatever the reservations about the book, it is a genius score, with more pearls than most could hope for in a lifetime. The original cast album, recorded after the show closed, is a marvelous artifact of Angela Lansbury’s first musical and, hey, Lee Remick should’ve done a few more.

***

“Nature never fashioned a flower so fair.”

1971: Sondheim and James Goldman’s Follies opens at the Winter Garden Theatre. A gorgeous and bittersweet love letter to so much that’s temporal, it is one of the few musical works that remains genuinely haunting, like a vision in vapors. Probably best they didn’t stick with the plan to have it be a murder mystery.

Until next week!