Or, How One Frame Sticks With You Into Adulthood

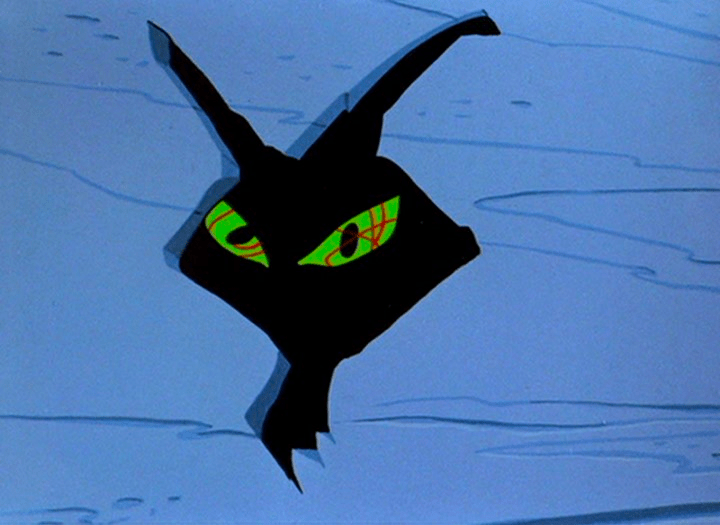

One shot in the animated special Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas! still terrifies me, and this is it:

Rights to the owners, as usual.

Yep, this one. Not that shot of the Grinch staring down from his cave with a sour frown of his ilk, not the malicious, blossoming smile of the Wonderful, Awful Idea, not even the Grinch seemingly leering at a bed of sleeping Who children (to affect Seuss’s typographic styling). This shot.

And I marvel at it with each viewing. Perfection.

Why?

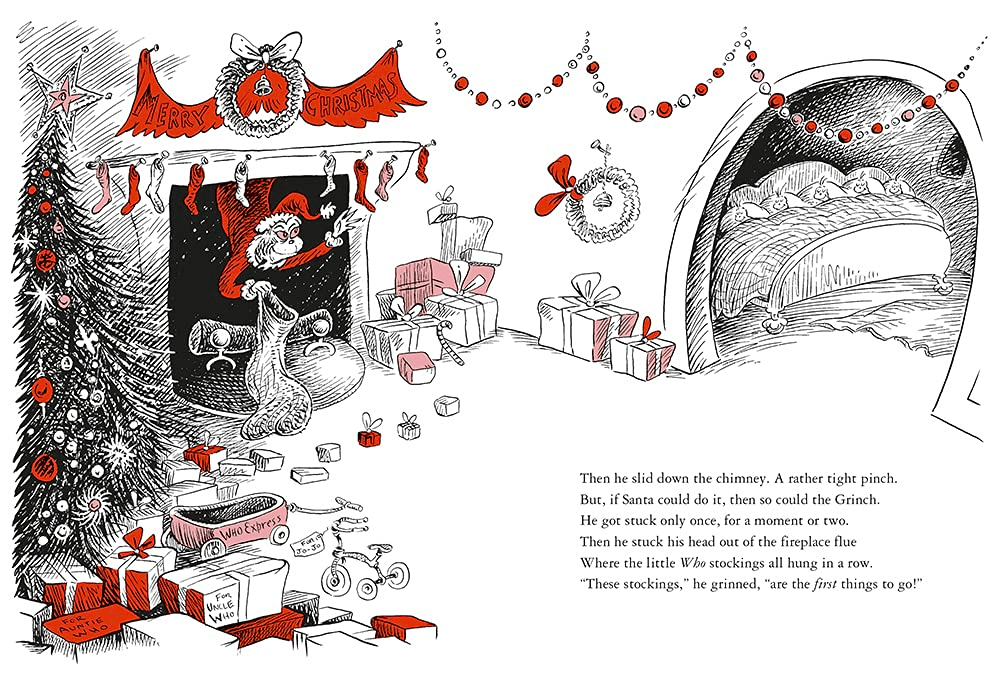

In transmuting Seuss’s text and the original 28 red, pink, and black ink illustrations to the small screen, director Chuck Jones and his team recreated most of the author’s tableaux. The chimney shot, however, has no direct equivalent in the book. There, the protagonist’s entry into the house of J. P. Who is a two-page spread is staged as an otherwise cozy Christmas scene.

A well-decorated living room with all the Yuletide trappings while children sleep in an adjoining chamber is disrupted by the Grinch snaking his way in from the flue to swipe the little Who stockings. For the special, Jones split Seuss’s illustration into two shots: first the fireplace with eyes, and then an angular shot of the Grinch employing a patented cartoon magnet to pry the stocking nails out of the mantlepiece. (Only in an animated universe would such nonsensical techniques be employed for such a task while being the only sensible way such a task could be done in said universe.)

But again, why should the aforementioned tableau be so unsettling but so appreciable at the same time? And why does it exemplify yet again why this special is one of the masterpieces of its kind?

Easy explanations abound: disembodied eyes disquiet; it’s like the monster under the bed; the darkness lets the imagination work. I could wax further in this general vein.

Getting more precise, however, yields more excellent discoveries.

Notably, this moment is the only time in the special that the Grinch’s eyes are shown on their own without the rest of his figures in view. Jones regularly used this device for unsettling moments in his Warner Bros. shorts. The best example can be found in the bloodshot green sclera of the homicidal rodents of the Dry Gulch Hotel in Claws for Alarm.

For a character otherwise visible like the Grinch, the “eyes only” choice is doubly important. Apart from the scowling mouth and jigsaw dentures, the Grinch’s eyes are his primary conveyors of menace. Given the restrained number of vocalizations the character gets (not to be confused with the narrator’s interjections), the eye’s capacity for expression accomplishes much. Jones also uses them for expert shifts in storytelling. Over a flashforward fade, for example, the Grinch’s right pupil becomes the doorknob to the Who children’s playroom, while Cindy-Lou Who’s strawberry is morphed into the left pupil to end the flash-forward.

Attentive viewers have long noted how the Grinch’s oculi go from red and jaundiced to baby blue (twice, in fact) in the finale as a sign of his revelation and reclamation. In the chimney sequence, however, they emerge as beacons of malice ready to strike from the shadows.

Here, as in almost every frame of the special, the contributions of Maurice Noble’s layouts and production design are everything we need and everything that demands special notice and admiration. In the shift from Seuss’s illustrations to a full-color world, Noble imbued the Whos with a mid-century whimsy in the ribbon poofs, the “MERRY CHRiSTMAS” banner, and the Who stockings. Doom is coming, however, for these proudly tranquil embodiments of Yuletide domesticity, as the audience is hapless to halt the Grinch’s impending ransack and sabotage.

Yet we all cheer him on.

The strength of the animated Grinch is his capacity to charm the audience into complicity with his activities. We are narrative captives along for the sleigh ride with this winking, leering, sinful sot. Cajoling the audience’s camaraderie is a unique attribute that most of Jones’s animated protagonist possess. They are always aware of the fourth wall and the audience. Indeed, the Grinch could easily speak or even sing Bugs Bunny’s immortal query at the end of Duck Amuck: “Ain’t I a stinker?” Stink, stank, stunk, no arguments here.

But the strength of the character is that his ironic self-awareness—something that explains the Grinch’s relatability and popularity—never needs to be acknowledged. The Grinch exudes it in every single frame with no explication necessary. Here is another reason why, for whatever success they have claimed, the more elaborate adaptations of the Grinch ultimately diminish the character by giving the audience too much explanation. The action and the image give all. Lurking in the brickwork here, the villain flashes yet another challenge, and Stockholm Syndromed into collusion, we surrender. We eventually get our say via the voice of the Unnamed Singer (whom every year becomes clearer as Max), who regales with “You’re a Mean One, Mr. Grinch,” an invective that even Cicero would have to admire for its rhetorical panache. Oddly enough, the Grinch’s eyes never occasion any mention in the song. But even then, the Grinch could seemingly care less about whatever musical harangue is thrown at him. Perfectly impervious.

Related, and to close, the narration of Boris Karloff at this point deserves distinctive praise in these shots. The baseline stillness of his reading of the text “Then he stuck his head out of the fireplace flue” ascends to seemingly angelic admiration with “Where the little Who stockings.” But a brief pause slides the tone back into something mocking with the line’s end: “hung all in a row.” Echt Grinch.