farrago, n. — A confused group; a medley, mixture, hotchpotch.

It is the intention to post a “farrago” of notable anniversaries and birthdays for the full calendar week (Monday through Sunday), but as it is midweek, this installment will start out a little abbreviated.

These farrago will by no means be exhaustive, but they will—hopefully—not lack fascination.

MARCH 11

1867 – Verdi’s Don Carlos premieres in Paris in its initial French-language iteration. While Otello and Falstaff unequivocally remain supreme constructions, this grand opera is my favorite of all Verdi’s stage works, in either/any of its versions.

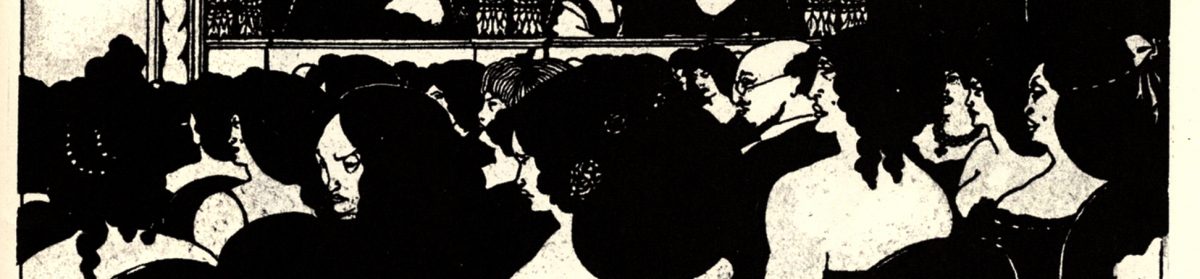

In many hands, the opera is a period piece de jeur but in the hands of the always provocative but always incisive Peter Konwitschny, that enemy to the friends of dead opera, Don Carlos takes on a visceral political context. Here is the climax of act three, the auto-da-fé before Valladolid Cathedral.

1950: The second version of Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony no. 4, op. 112, debuts on a radio broadcast with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Sir Adrian Boult. (The first concert performance under Gennady Rozhdestvensky does not take place until 1957.) Fresh off the success of his Fifth Symphony, Prokofiev sought to rehabilitate the first version of his Fourth Symphony, originally premiered in Boston in November 1930. Not long after completing the in 1947, however, Prokofiev was denounced and accused of formalism in the “Zhdanov Decree” of 1948. The expanded Fourth develops further the material Prokofiev adapted from his ballet The Prodigal Son, resulting in an epic canvas unique among the composer’s symphonies.

1957: The Lady Chablis is born in Quincy, Florida, but she forever belongs to Savannah: “I’m not a fictional character, honey. I am for real.”

MARCH 12

Happy Birthday to the divine and essential Lesley Manville! Here in conversation with director Mike Leigh.

MARCH 13

1781: Architect, artist, and designer extraordinaire Karl Friedrich Schinkel is born in Neuruppin in Brandenburg. His design for the 1816 production of Die Zauberflöte at the Hofoper Unter den Linden may well be the most iconic opera set ever designed.

1892: Journalist Janet Flanner (the “Genêt” of New Yorker fame) is born in Indianapolis: “I keep going over a sentence. I nag it, gnaw it, pat and flatter it.”

1954: The animated short Bugs and Thugs is released. Another installment of Bugs’s misadventures with the diminutive Rocky and the moronic Mugsy, the short recycles many of the precepts director Friz Freleng introduced in his earlier 1946 Racketeer Rabbit. Foremost among them is the “fake cop” routine, wherein Bugs imitates a whole police squadron, who promptly show up thereafter.

March 14

1853: Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler is born in Bern. How I ended up in the upper right hand corner of his painting Die Nacht (1890) I’ll never know.

1887: Sylvia Beach is born in Baltimore. One of the great American expats living in Paris between the World Wars, Beach founded the bookstore Shakespeare and Company and famously published Joyce’s Ulysses in full in 1922.

1934: Jazz organ legend Shirley Scott is born in Philadelphia.

1965: György Ligeti’s Requiem debuts in Stockholm with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Michael Gielen. Perhaps the most recognized of his compositions, the Requiem shows off the composer’s command of a highly intricate polyphony. The work took on a new life after Kubrick’s use of the “Kyrie” section in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Until next week.